When Kresge College opened to students in 1973, journalists had no idea what to make of this earnest, rebellious, fiercely independent place and its spirit of participatory democracy.

With its red-and-yellow color palette, asymmetrical buildings, isolation in the redwoods on the north side of campus, and its strong emphasis on student-driven education, Kresge did not look, act, or function like any other academic community in the United States.

Watch: A better version of itself

"An environment to learn. An environment that promoted a lot of experimentation."" — Paul Simpson (Kresge ‘02, business management economics)

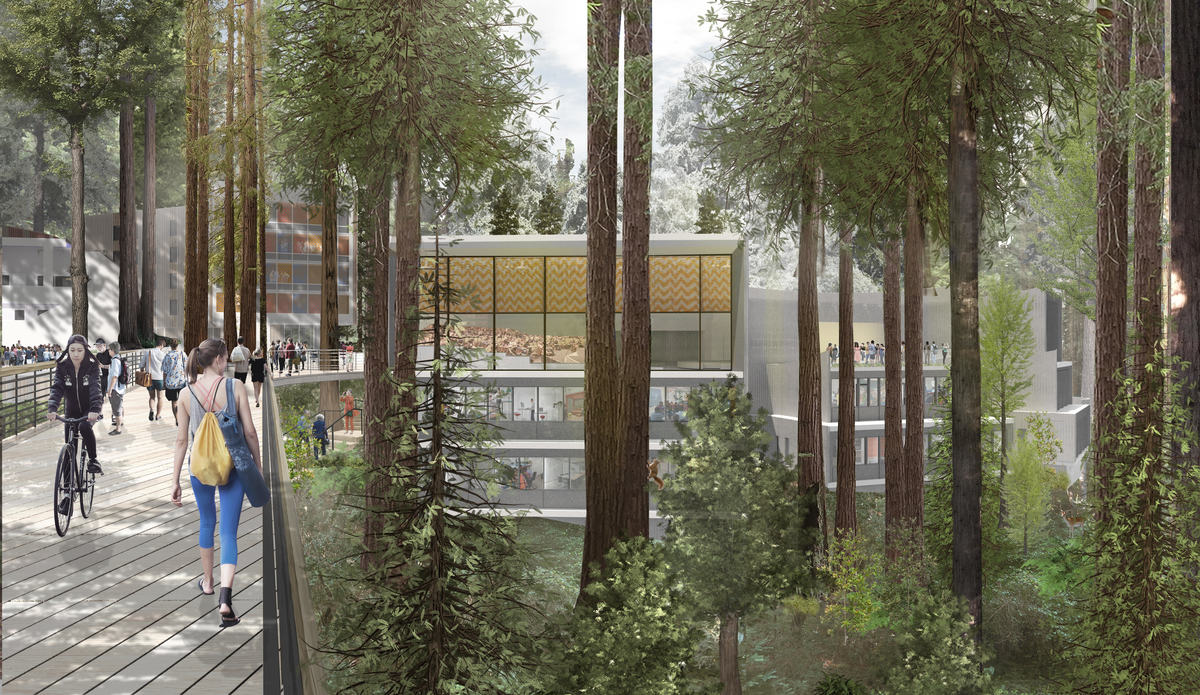

Kresge College’s iconic community-focused architecture began in the late 1960s in a process led by students. Starting 15 years ago, with the awareness that the structures were reaching the end of their service lifespan, Kresge reconvened that student-driven design process. The resulting design represents a new way of seeing the Kresge community, while preserving the elements that make the college an ideal setting for independent thinking and participatory democracy.

UC Santa Cruz’s sixth residential college started out as an impassioned critique of trends in American education during the Cold War years, from anonymous “mega-versities” to dorms as big as urban high-rise apartment complexes.

Kresge was more than willing to delve into experimental territory and follow the will of its student population—and its architecture, designed by famed postmodernists Charles Moore and William Turnbull of Moore Lyndon Turnbull Whitaker and lauded by the architectural community, supports that spirit.

In fact, the college was so daring that some education reporters for the country’s biggest newspapers seemed flummoxed by the place. The Los Angeles Times alternately hailed Kresge as “one of the most ambitious (higher educational) experiences on the West Coast” and mocked Kresge for its “touchy-feely” approach.

This mixed feedback was inevitable, considering Kresge’s refusal to embrace the mainstream. For example, Kresge students formed intimate “kin groups” for small-group learning, mixing academic and social life. While other colleges hired armed police for security, Kresge paid students $7 a night to patrol the grounds while “armed with nothing but the ethic of individualism,” one early faculty member observed.

An extension of the family

The college’s original 270 students were organized into these small clusters, which were meant to be the center of their academic life. Each group also included a professor and a handful of staff members. These kin groups were turned into small and intimate seminars. Gary Chase, a freshman in the original cohort of Kresge undergraduates said, in an interview in 1972, that kin groups “act as an extension of the family.”

In 1972, the Los Angeles Times reported that “social and interpersonal side of the kin groups appeared to be flourishing,” but quoted several faculty members who thought of these groups as a “touchy-feely” waste of time.

But the college got an enthusiastic evaluation from a distinguished sociologist, Phillip Slater, who spent time at Kresge in the early 1970s, and declared the place was a “powerful intellectual stimulus to students and faculty. Kresge students are able to think rather than merely push pieces of paper around. They can transcend the frames that strangle most academic thinking.”

Kresge, in other words, was a free-spirited place. “We used to have hot tubs here and a sauna,” said Kresge programs coordinator Pam Ackerman. “And yes, students ran around naked!”

These days, the kin groups have fallen away, but Kresge retains its environmental focus as well as its feisty, independent spirit with an emphasis on hands-on, interdisciplinary education.

A need for renewal

Forty-five years later, the educational mission and design of Kresge have not gone out of date.

Alas, the original buildings have not fared so well. Walk through the place, and you will see signs of wear—holes in the original stucco, for example, with wood paneling and wires poking through.

Kresge’s aging infrastructure poses a challenge, said UC Santa Cruz’s senior architect and interim campus planner Jolie Kerns. How can the college maintain the educational and architectural integrity and vitality of the original Kresge while updating the college experience for today’s students?

In addition, how can the college—which was built two decades before the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act—best be brought up to speed with current accessibility laws?

In response to these questions, UC Santa Cruz is in now in the design phase of a proposed renewal project—essentially an infill construction project that will mix the renovation of existing buildings with new construction. Of Kresge’s 21 existing buildings, 11 will be renovated and rebuilt. Others will be removed to make way for new viewsheds, commons, gathering spaces, and accessibility features, including a “stramp” (a hybrid staircase and ramp) for wheelchair users. Buildings meant for similar uses—living, learning, support—will be grouped together rather than sprinkled haphazardly or placed inconveniently far from each other.

Plans for the north section of the Kresge campus would include new and larger residence hall accommodations; a new academic plaza and academic facility; the Kresge provost’s offices and classrooms, including a 600-seat lecture hall, which would become the largest of its kind on campus; a 150-seat lecture hall; and 50- and 35-seat classrooms. A 48-seat computing lab is also included.

The renewal project will also include better wayfinding and improved access to and from the rest of campus, said Kerns.

“Improved connectivity is a vital part of this project,” she said. The intent, she continued, “is to balance the new and the old.”

Another dramatic new feature will be new residential buildings with 400 beds intended for first-year students. (The 400 beds are not all net new beds—they’re replacing some of the existing 368 beds. After the renewal, Kresge will have 550–575 beds total.) This will constitute a lifestyle change for Kresge, which has, exclusively, apartment-style living with kitchenettes for students. But these new buildings will continue to sustain that “independent living” model, with communal kitchens where students can cook their own food. There will be about 33 students per floor.

Preserving beloved landmarks

The majority of existing Kresge residential buildings will be renovated, which will be set aside for continuing students. These buildings will have both apartments and other styles of living arrangements.

The renewal plan will preserve many key elements of Kresge College, including some beloved familiar landmarks that will stay as is: the famous Kresge piazzetta and the legendary “waterfall steps”—often referred to, winkingly, as the “acid steps” because some people trip while walking on them.

Also remaining: the quirky “mayor’s stand” (a quaint name for a small tower with a stairwell and a platform that makes it a great place for speech-making); the Writing Center (which will be repurposed as the Kresge Student Faculty Center, with the writing center moved elsewhere), and the canary-yellow coin-op Laundromat.

Though the existing Town Hall will be demolished, its beloved, unframed silkscreen images of performers and speakers who have graced its stage will be retained. A new Town Hall will be built in the southern end of the Kresge campus, opening onto an outdoor plaza.

The planners also mentioned that the new project would increase “accessibility and the sense of arrival,” while building upon “the founding spirit and intentions of Kresge college.”

The UC Regents have given preliminary approval for the project for the design phase, but the planners must go before the Board of Regents again in March to seek approval for the full project.

Collecting input

The project developers have been holding once-a-month meetings at the Kresge Town Hall, soliciting input. The project is also subject to an environmental impact report, a draft of which was released Nov. 15 for a 45-day public review.

Chancellor George Blumenthal noted that UC Santa Cruz has long had plans to renovate Kresge.

“Kresge, as it approaches its 50th year, is in desperate need of repairs, but that’s only part of the picture,” Blumenthal said. “As a public university, we also need to make sure each of our colleges is welcoming and accessible to all of our students, including those with disabilities. The renewal project will retain the beauty and wonderful character of the original design while also being more responsive to the needs of today’s student population.”

Kresge students have a strong sense of ownership about their college. Not surprisingly, the renewal project has been a hot topic of conversations and impassioned debates at the college.

Ian Thad Gregorio (Kresge ‘19, literature) said that the redevelopment is long overdue. He’s glad the project will address the “awkward interaction” between classrooms and residential buildings, which are so close together that “you can’t be too loud in your rooms, or in your classes” without it impacting your neighbors.

He also said he was pleased to see that the new permutation of Kresge would have a strong emphasis on “common spaces that promote students talking to each other and coming together in and outside the res halls. This will create more central areas for people to meet, and that, personally, is the most important thing for me.”

For Gregorio, the renewal plan has been delayed much too long. “It’s finally Kresge’s time,” he said.

Bradley Jin (Kresge ‘19, sociology and feminist studies with a minor in physics) said he is “of two minds” about the project.

“On the one hand, this can’t happen soon enough,” said Jin, mentioning the decay of the buildings and related issues. “On the other hand, there are parts of the redevelopment, as it stands right now, that I don’t really like.”

It’s especially painful to lose the original Town Hall. “There is such a history there,” he said.

He’s also disappointed that the renewal plan will diminish the original number of Kresge apartments, with new res halls being built instead.

“There will be an increase in square feet, which is great, but it sort of removes what makes Kresge special to me—the independent living, the apartments, and having your own space,” Jin said.

Kerns agreed that the independent living element is a major part of Kresge’s history and character.

“The new residence halls will include communal kitchens on each floor, so that students can continue to have the sense of community that comes with cooking and eating together,” she said. “Apartments will still be a vital part of the living experience for continuing Kresge students.”

Logistics and details

Builders expect to begin the first phase of construction in fall 2019, with completion expected for 2023. Kresge students will continue to live at the college during the construction. The project will add new spaces for student life and support, including a student co-op; easier access for disabled students and visitors; an increase in bed spaces from 368 to 550–575; and better connection to the rest of campus via UC Santa Cruz’s scenic North Bridge. This project would also grow the footprint of Kresge from 133,000 to 200,000 square feet.

The total project budget is still being finalized, though the current projection is about $250 million, including $50 million earmarked from general financed funds from the state for the renewal and expansion of academic spaces. This project is not a public-private partnership. Instead it would use state funds for academic space and housing funds for the residential aspects.

Kresge provost Ben Leeds Carson said the project will sustain the spirit of the original design while serving the needs of the 21st-century student community.

“Charles Moore’s sense of angularity and contour, and innovative approaches to lines of sight, will be retained in the new design,” said Carson, an associate professor of music. “Among the purposes (of the renewal plan) is to open the space up a little bit.”

Most of the original buildings will be left intact, but renovated and updated. As for the new construction, “it relates in complementary ways to the existing architecture, but introduces elements of openness, clarity, and a sense of connection to the rest of campus,” Carson said.

Kerns, working closely with Studio Gang and TEF Design, said she envisions a project that sustains Kresge’s existing architecture and community while creating new spaces of participation for students.

Studio Gang is the architectural firm of Jeanne Gang, noted architect and MacArthur Fellow whose firm is based in Chicago with offices in New York and San Francisco. Gang—recognized as one of the most prominent architects of her generation—is credited with advancing the possibilities of architecture and design in the 21st century, including their ability to make a positive social and environmental impact.

News of the redevelopment project has drawn passionate responses ranging from those who think the aging complex should be “demo’d” to those who believe the sanctity and the atmosphere of the original development will be wrecked with major new changes.

In contrast, Ackerman, the Kresge programs coordinator, said the project in the long run will be good for the Kresge community, though she also has a sense of loss.

“It was built by a famous architect, [Charles Moore], and the design is very important to people who follow architecture,” Ackerman said. “It won’t have the original flavor. It won’t be the same Kresge, but it will be better in the long run. It will be earthquake sound. I think it is not practical to have it look just like the original. I think we have to move past that. What’s important is it will be ADA compliant.”

A walking tour of old and new

On a sunny, breezy day in late summer, Kerns led a walking tour of the Kresge complex to show what will change and what will stay the same.

To start off the walk, Kerns asked a group of visitors to gather on the beautiful bridge that passes over a redwood-lined ravine and connects to Heller Drive.

The view was lovely, but Kerns didn’t bring people there for the sake of sight-seeing. She wanted to talk about a pressing issue: the lack of accessibility for those with disabilities.

“If you were mobility impaired and were on campus and wanted to get to Kresge, you would be going all the way down past Porter College to the bus stop between Oakes and Porter on Heller Drive.” The bridge and ramp would provide an accessible connection from Heller Drive.

As Kerns walked on, she pointed to the buildings that would be demolished, including the R8 apartment building, which will be replaced with an outdoor series of rooms that will continue to hold the edge of the street; R7; and R5, whose removal will provide key access to the “backyard” and new residential buildings. Building R11 will be removed to open up a larger civic plaza anchored by the new Town Hall, and R3 will be removed to to make way for a “stramp”—a zig-zagging ramp-stairway hybrid that provides a new accessible path through the college, facing the Civic Plaza and Town Hall in the south of the college.

Large portions of the iconic Kresge architecture will be refurbished to retain their same shape, look, and color, but with more durable materials. As for the second-growth redwoods around the Kresge complex, “yes, some will be removed, but the new buildings are designed to weave around as many existing trees as possible,” Kerns said, noting that the campus will work with an arborist to try to minimize impact to “substantial groves of redwoods.” The new construction is designed to minimize the number of trees that have to be removed by bending around significant groves and nestling into the existing topography.

Other features will include: a new Owl’s Nest Café, which will be rebuilt close to its current site at the front of the Academic Plaza, and a “pedestrian trail” that will weave in and out of the cluster of three new residential halls.

The design of the Academic Building will have windows facing the north campus light streaming across the ravine, Kerns said. She added that the renewal project will be built with this light in mind, and with more points of access into the surrounding forest.

A history of innovation and critical thinking

Kresge made national news when it opened to students in 1972 with $600,000 from the Kresge Foundation—the family who put the “K” in Kmart, which was founded by S.S. Kresge.

Much of the hype, as well as the negative publicity, focused on the “T-group movement,” which encouraged better human relations and problem solving through sensitivity training and “encounter” groups. The T-groups, or training groups, influenced the original Kresge, which even had a “10 commandments of T-group,” according to Gerald Grant and David Riesman, whose 1978 book, The Perpetual Dream: Reform and Experiment in the American College, includes a richly detailed portrait of early Kresge.

Among those commandments: “Do not assume we know anyone’s feelings except our own,” “attend to the here and now,” “don’t be defensive,” and “don’t use openness as a weapon.”

The college’s founding provost, Robert Edgar, believed so passionately in Kresge’s educational mission—with a strong focus on environmental studies, along with an unusual degree of student involvement and radical self-determination—that he gave up a prestigious post at Caltech, where he was a distinguished geneticist, isolating viruses in his lab, to work at UC Santa Cruz.

Edgar’s commitment to undergraduate growth, risk taking, and creative development became stronger than his love of research. During an interview with the Los Angeles Times in 1973, Edgar complained about the “growing feeling of incongruity” between the scientific training that undergraduates were getting in the classroom and their ability to understand the implications of their work.

“They were totally unprepared,” he said.

Edgar envisioned a future in which he and his students would relate to each other, and he could talk more directly to them, rather than just talking at them from the front of the room. He believed that students needed a better sense of their own personal worth, and their ability to make positive change, by taking part in an egalitarian living and learning community.

Edgar was influenced by the psychologist Michael Kahn, who was steeped in group training techniques that placed a premium on communication skills and interpersonal dynamics. Kahn co-taught a course with Edgar called Creating Kresge College. Students did much more than go to class. They had an active role in designing Kresge’s original curriculum, even serving on committees that had a hand in personnel decisions and budgetary matters.

In fact the T-group structure meant so much to the foundational Kresge that it influenced early hiring decisions. If potential faculty were unwilling to go away for “weekend T-group experiences,” Kresge would not hire them, according to The Perpetual Dream.

The students put such a high premium on autonomy that they attempted at one point to have Kresge secede from the rest of the campus. They even had their own college newspaper, the Kresge Town Krier, which, in its first incarnation, was written on an old-fashioned typewriter and put together using the traditional “cut and paste” layout.

“Totally theatrical” architecture

At Kresge’s opening, its architecture was every bit as cutting-edge as its educational mission. The human scale of the college, with its inviting piazzetta, the mayor’s stand, the waterfall steps, and unique “cut-out” design, made it look like a minimalist stage set based on a remote Italian hill town.

Its relative isolation also reinforces this village-like feeling. Other colleges were located close to the main thoroughfares of campus, but Kresge was way up in the forest, a third of a mile from Heller Drive. Just getting there was a trip in itself.

Kresge College is internationally famous for its architecture, and for good reason. It makes an unforgettable first impression. Along the winding central street, rows of residential buildings present with varying heights and shapes—a strong visual metaphor for Kresge’s rebellion against uniformity. Irregular “cut out” shapes of portals and pillars frame the upper levels of its galleried walkways.

Seemingly out of nowhere, a cluster of young redwoods rise up from a small plot of land between two residential halls. A long walkway moves steadily uphill past a series of murals. Everywhere you look, a new surprise awaits—a free library, a view into the forest, a row of yellow smiley-face planters.

Paul Heyer, in his 1993 book American Architecture, called the look of Kresge “totally theatrical,” with painted-stucco buildings that looked as though they were “almost dancing through the landscape.” Heyer rhapsodized about the “irregularly punctured false fronts,” splashed with primary colors. The entire Kresge complex seemed to rebel against “the traditional campus hierarchy of buildings and spaces, sequential, predictably shaped and axially related.”

To design this village-style college, UC Santa Cruz retained the architect Charles Moore and William Turnbull of Moore Lyndon Turnbull and Whitaker, who clustered its residential, academic, and social buildings around a pedestrian street. His grand creation—the subject of several books and countless architectural journal articles, and praised by legendary architect Frank Gehry—looked like a futuristic movie set.

The design, heavily inspired by Mediterranean villages, has white-washed stucco buildings, while certain structures that face the redwood forest have a brownish color that makes them blend with the trees behind them. Remarkably for the early 1970s, student dorms were not only co-ed, but also occupied the same buildings as the classrooms and in some cases the professors’ offices. The buildings, and the layout of Kresge, reinforced the values of integrated living and learning while promoting student interaction.

This design has been celebrated in many architectural journals and newspaper stories. In an article that appeared in the New York Times in 1980, the noted architectural critic and arts writer Paul Goldberger—later the biographer of architect Gehry—called Kresge college a “masterwork … an Italian village more than anything else, with little plazas and streets and buildings huddled close together.”

He also praised “the bold and colorful graphics characteristic of the work of Charles Moore, the California architect, and a general sense of wit and exuberance.” In fact, Gehry himself, appearing on campus in 2013 as part of the UC Santa Cruz Founders Celebration, singled out Kresge for special praise. “Charles Moore did a nice piece,” he said.

The college feels like a world apart, even within the confines of the UC Santa Cruz campus, which is several miles away from downtown Santa Cruz. This was by design; Kresge was originally intended to be as self-reliant and self-contained as possible.

But Carson, the Kresge provost, said that the original design was always meant to be “dynamic,” and responsive to the changing needs of the campus community. He noted that the original Kresge design has an “inward focus” with residential halls facing each other along the narrow walkway. There are currently few spaces at Kresge that open up to the forest canopy that surrounds it. In contrast, the renewal additions will include a new academic building that seems to gaze out into the forest beneath the connecting bridge, and toward the rest of campus. There will also be new signs for easier navigation, as well as new architectural flourishes clearly establishing the north and south entrances to Kresge.

As a result, Carson said, the new incarnation would make it easier for visitors to access Kresge while retaining the college’s unconventional spirit and its “village” atmosphere.

“Whatever makes UC Santa Cruz distinctive within the UC system, Kresge is distinctive in that way within UC Santa Cruz,” Carson said. “We are the UC Santa Cruz of UC Santa Cruz.”