A UC Santa Cruz special report: Neutron stars, gravitational waves, and all the gold in the universe

Astronomer Ryan Foley says observing the explosion of two colliding neutron stars–the first visible event ever linked to gravitational waves–is probably the biggest discovery he’ll make in his lifetime. That’s saying a lot for a young assistant professor who presumably has a long career still ahead of him.

So what makes this strange cataclysm in another galaxy so exciting to astronomers? And what the heck is a neutron star, anyway?

A neutron star forms when a massive star runs out of fuel and explodes as a supernova, throwing off its outer layers and leaving behind a collapsed core composed almost entirely of neutrons. Neutrons are the uncharged particles in the nucleus of an atom, where they are bound together with positively charged protons. In a neutron star, they are packed together just as densely as in the nucleus of an atom, resulting in an object with one to three times the mass of our sun but only about 12 miles wide.

“Basically, a neutron star is a gigantic atom with the mass of the sun and the size of a city like San Francisco or Manhattan,” said Foley, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

These objects are so dense, a cup of neutron star material would weigh as much as Mount Everest, and a teaspoon would weigh a billion tons. It’s as dense as matter can get without collapsing into a black hole.

The merger

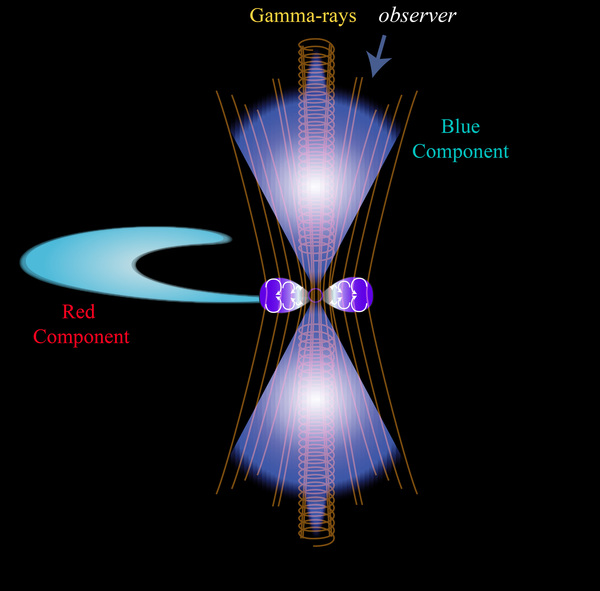

Like other stars, neutron stars sometimes occur in pairs, orbiting each other and gradually spiraling inward. Eventually, they come together in a catastrophic merger that distorts space and time (creating gravitational waves) and emits a brilliant flare of electromagnetic radiation, including visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light, x-rays, gamma rays, and radio waves. Merging black holes also create gravitational waves, but there’s nothing to be seen because no light can escape from a black hole.

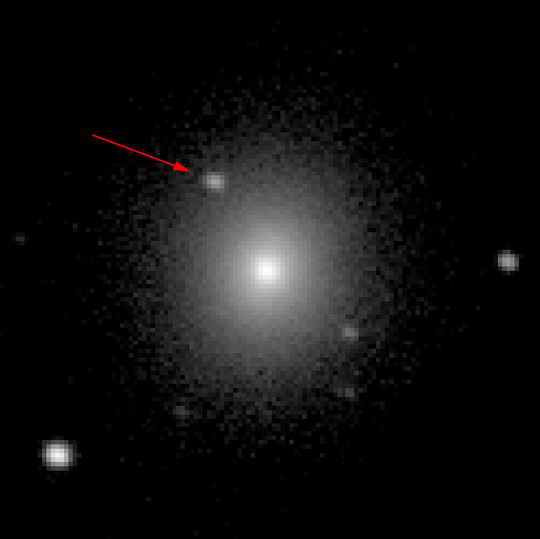

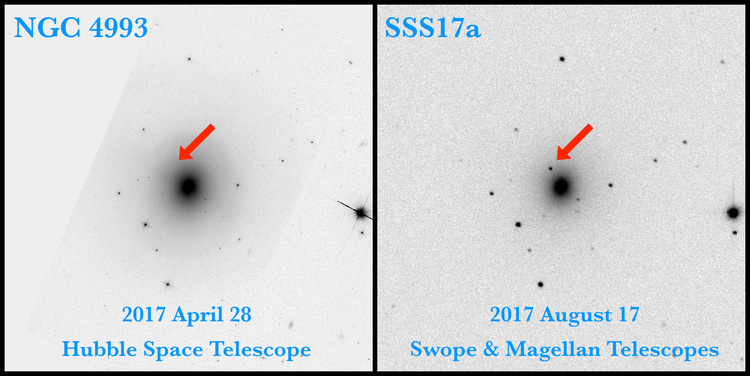

Foley’s team was the first to observe the light from a neutron star merger that took place on August 17, 2017, and was detected by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Now, for the first time, scientists can study both the gravitational waves (ripples in the fabric of space-time), and the radiation emitted from the violent merger of the densest objects in the universe.

It’s that combination of data, and all that can be learned from it, that has astronomers and physicists so excited. The observations of this one event are keeping hundreds of scientists busy exploring its implications for everything from fundamental physics and cosmology to the origins of gold and other heavy elements.

All the gold in the universe

It turns out that the origins of the heaviest elements, such as gold, platinum, uranium—pretty much everything heavier than iron—has been an enduring conundrum. All the lighter elements have well-explained origins in the nuclear fusion reactions that make stars shine or in the explosions of stars (supernovae). Initially, astrophysicists thought supernovae could account for the heavy elements, too, but there have always been problems with that theory, says Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz, professor and chair of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz.

A theoretical astrophysicist, Ramirez-Ruiz has been a leading proponent of the idea that neutron star mergers are the source of the heavy elements. Building a heavy atomic nucleus means adding a lot of neutrons to it. This process is called rapid neutron capture, or the r-process, and it requires some of the most extreme conditions in the universe: extreme temperatures, extreme densities, and a massive flow of neutrons. A neutron star merger fits the bill.

Ramirez-Ruiz and other theoretical astrophysicists use supercomputers to simulate the physics of extreme events like supernovae and neutron star mergers. This work always goes hand in hand with observational astronomy. Theoretical predictions tell observers what signatures to look for to identify these events, and observations tell theorists if they got the physics right or if they need to tweak their models. The observations by Foley and others of the neutron star merger now known as SSS17a are giving theorists, for the first time, a full set of observational data to compare with their theoretical models.

According to Ramirez-Ruiz, the observations support the theory that neutron star mergers can account for all the gold in the universe, as well as about half of all the other elements heavier than iron.

Ripples in the fabric of space-time

Einstein predicted the existence of gravitational waves in 1916 in his general theory of relativity, but until recently they were impossible to observe. LIGO’s extraordinarily sensitive detectors achieved the first direct detection of gravitational waves, from the collision of two black holes, in 2015. Gravitational waves are created by any massive accelerating object, but the strongest waves (and the only ones we have any chance of detecting) are produced by the most extreme phenomena.

Two massive compact objects—such as black holes, neutron stars, or white dwarfs—orbiting around each other faster and faster as they draw closer together are just the kind of system that should radiate strong gravitational waves. Like ripples spreading in a pond, the waves get smaller as they spread outward from the source. By the time they reached Earth, the ripples detected by LIGO caused distortions of space-time thousands of times smaller than the nucleus of an atom.

The rarefied signals recorded by LIGO’s detectors not only prove the existence of gravitational waves, they also provide crucial information about the events that produced them. Combined with the telescope observations of the neutron star merger, it’s an incredibly rich set of data.

LIGO can tell scientists the masses of the merging objects and the mass of the new object created in the merger, which reveals whether the merger produced another neutron star or a more massive object that collapsed into a black hole. To calculate how much mass was ejected in the explosion, and how much mass was converted to energy, scientists also need the optical observations from telescopes. That’s especially important for quantifying the nucleosynthesis of heavy elements during the merger.

LIGO can also provide a measure of the distance to the merging neutron stars, which can now be compared with the distance measurement based on the light from the merger. That’s important to cosmologists studying the expansion of the universe, because the two measurements are based on different fundamental forces (gravity and electromagnetism), giving completely independent results.

“This is a huge step forward in astronomy,” Foley said. “Having done it once, we now know we can do it again, and it opens up a whole new world of what we call ‘multi-messenger’ astronomy, viewing the universe through different fundamental forces.”