A UC Santa Cruz special report: Work hard, play hard: Life according to renowned biochemist Harry Noller

Harry Noller starts his day with a cappuccino and a chocolate doughnut, ordering in Spanish from a barista who greets him by name.

“The physicist Edward Teller once said science is the process of turning coffee into ideas,” Noller says, smiling, as he strolls from the coffee bar back to his office in Sinsheimer Labs on the UC Santa Cruz campus.

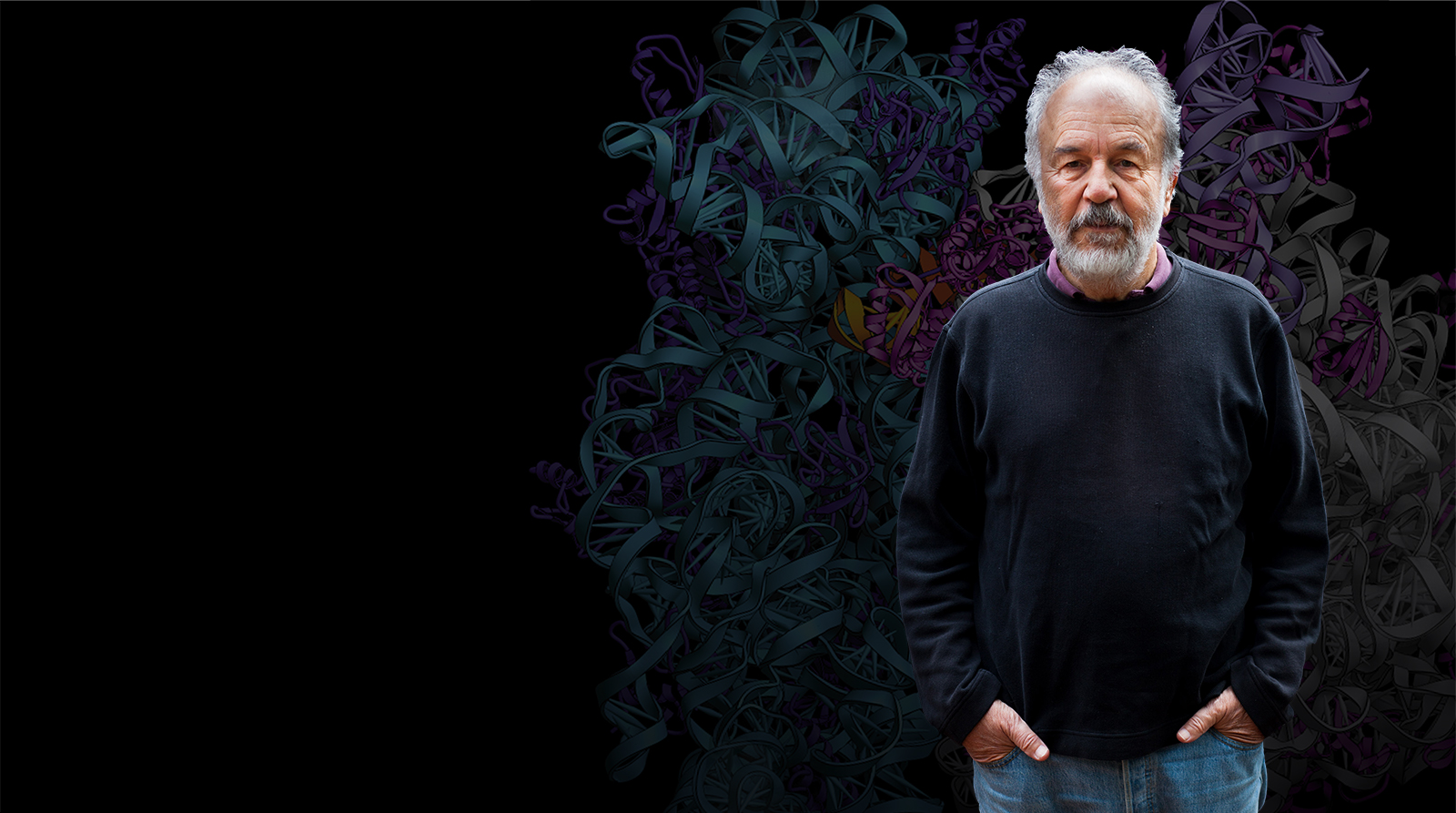

Professor emeritus of molecular, cell, and developmental biology, Noller has just received the 2017 Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences for his discoveries about the ribosome, the tiny structure of the cell that Noller calls the “mothership of life.” His insights are taking us right to the brink of understanding the very origins of life on the planet. It’s a monumental moment for this thoughtful, soft-spoken scientist whose accomplishments in the lab are rivaled by his passion for jazz and fast cars.

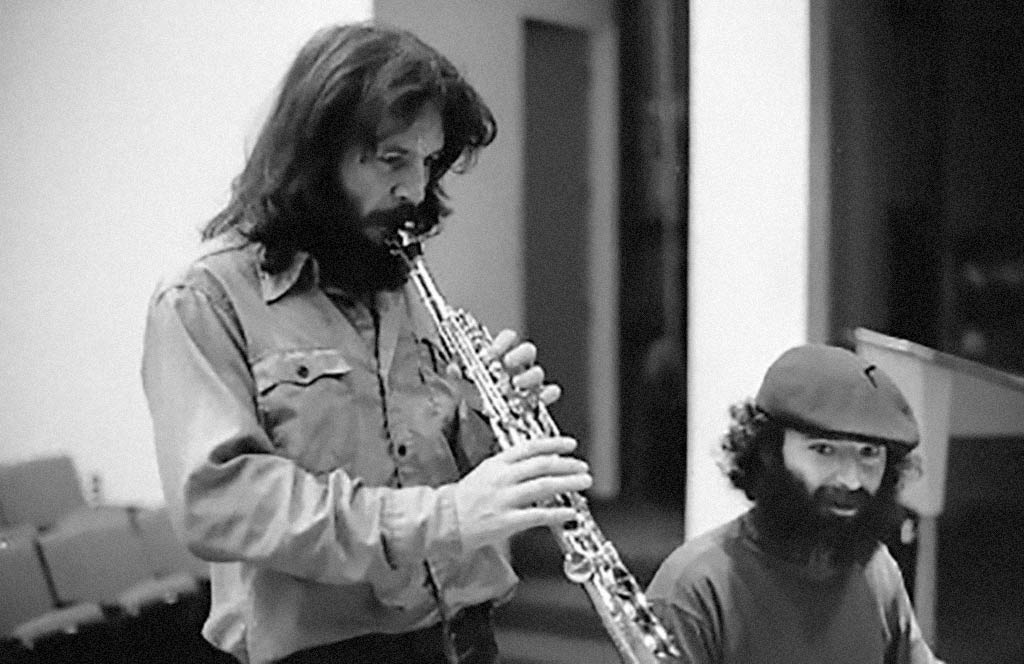

“My own philosophy is work hard, play hard,” says Noller, a lifelong musician who has played saxophone with Chet Baker and the Randy Masters Group. “Doing science is exciting, it’s a privilege. After working hard in the lab, it feels good to do other things. Playing jazz is a very special experience. Another part of me comes alive when I play. It sort of completes my feeling as a human being.”

“My office and lab are on the most beautiful campus in the world, where walking to the library is practically a religious experience.”

Noller still works in the lab every day, driven by the curiosity that has propelled his quest for answers for five decades. “The most exciting thing is what we’re doing right now,” he says. “Discoveries become old hat very quickly.”

That’s quite a statement from a man who helped upend what we know about the ribosome.

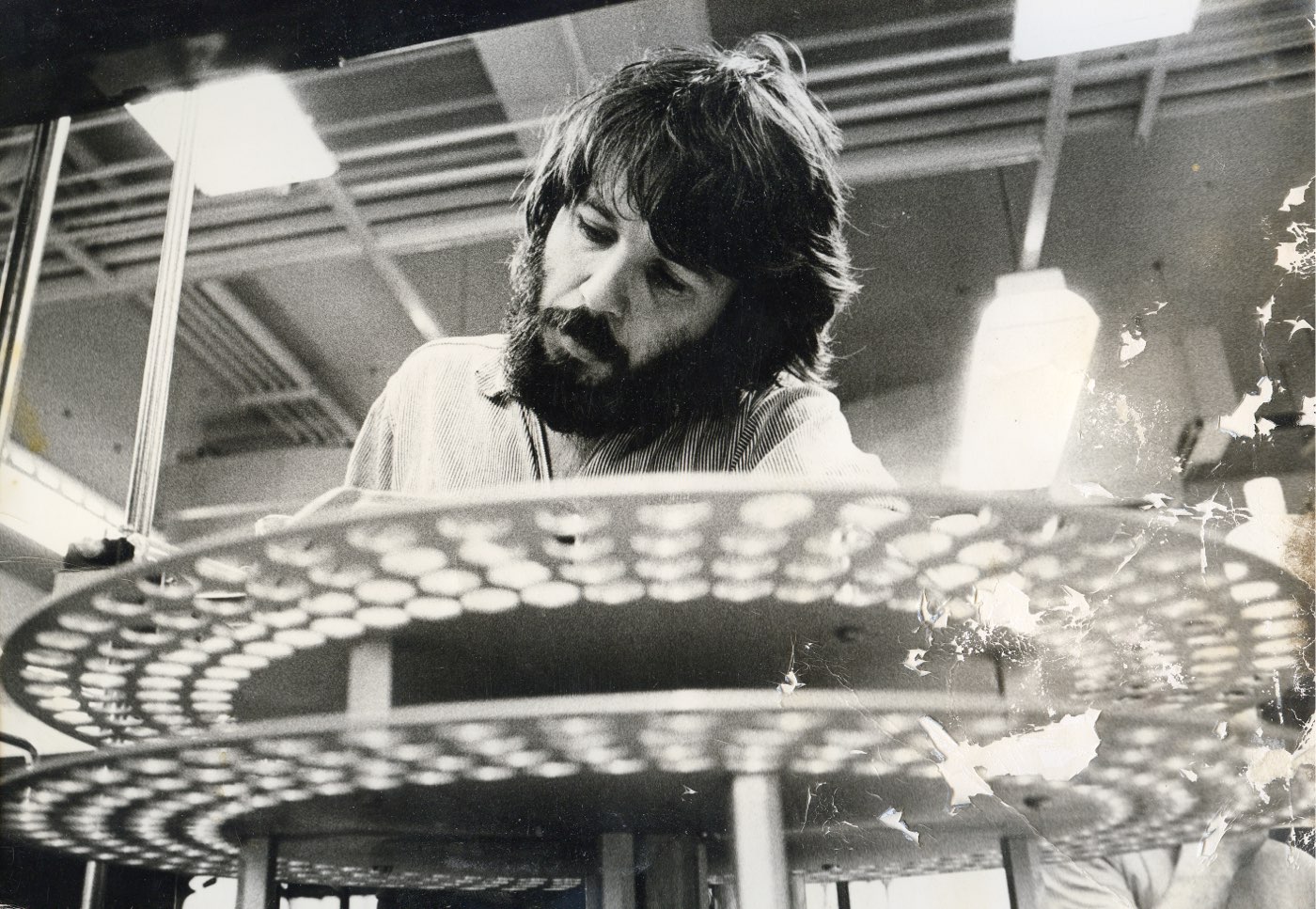

Noller’s career is marked by a determination to follow the science, even when it meant challenging conventional thinking. Like the jazz musician he is, Noller improvised, adapting to experimental results that stretched his own thinking and forced him to broaden his expertise. Early on, working in relative isolation on the young campus of UC Santa Cruz gave him the freedom he needed—no experts to squelch his ideas or dispute the direction of his research.

“There's that moment when you realize, ‘We're the only people in the world who know this.’ Those are rare moments.”

The paradox of scientific pursuit is that breakthroughs are frequently based on daring ideas and experimentation—creativity that is often initially rejected by the establishment. A distinguished biochemist at UC Berkeley dismissed Noller’s work in the mid-1970s as a “crackpot idea.”

“Scientists are very conservative. They have to be convinced,” says Noller, 77, who was an untenured assistant professor when he started shaking up the field of biochemistry. The process began with him. “I was a protein chemist, but the results were clearly showing we were going to have to start working on RNA, which I knew very little about.” He began to learn, quickly.

“We listened to our experiments instead of listening to other people,” recalls Noller.

The upside of not being taken seriously is that Noller’s team faced relatively little competition for the better part of a decade. But those years were marked by ups and downs in the lab, self-doubt, and plenty of “quiet desperation.”

Noller’s team slogged through a staggering amount of grueling work. Quoting The Firesign Theatre, Noller describes the challenge of scientific exploration as “everything you know is wrong.”

Long days in the lab were followed by jazz sessions that lasted until dawn.

“Playing jazz is a very special experience. Another part of me comes alive when I play.”

And then came the “ah ha!” moment.

“It’s a special thing when you discover something,” says Noller. “There’s that moment when you realize, ‘We’re the only people in the world who know this.’ Those are rare moments, but when they happen, you’re reminded: This is what it’s all about.”

To anyone who laments that Noller was overlooked when the 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry recognized breakthroughs in ribosome research, rest easy. Never one to look back, Noller’s attention is always focused on the next discovery. Although he didn’t set out to tackle what he calls the “ultimate question of science,” Noller is clearly on the threshold of, “Where do we come from?”

Quiet and unassuming in jeans and sneakers, Noller is welcoming, thoughtful, and deliberate. He chooses his words carefully; his gestures are subdued. This father of four and grandfather of eight doesn’t own a cell phone, and although he explains that there’s no signal at his home in rural Santa Cruz County, one suspects that he prefers to avoid the distraction, perhaps hinting at the discipline that underlies his success as a scientist and musician.

Persistence comes naturally to Noller, who describes the “thrill and terror” of opening for Duke Ellington—and the challenge of playing with avant-garde musicians so talented it “scares the hell out of you.” During college, he jammed every week with masters, including Pharaoh Sanders—often returning home late at night, driven to practice for hours more until his bleeding lips would force him to put down his horn. It’s not every biochemist who can hold his own with leading jazz artists, finding a groove that’s “almost telepathy” with the other musicians.

Like jazz, science demands structure and daring. “Science has a creative component to it,” says Noller. “Ideas that propel experiments come from a creative source. Scientists are often musicians, artists, people with diverse interests.”

Growing up in Berkeley, Noller was a curious boy whose parents, teachers, and neighbors nurtured his interest in the world around him. Although neither parent went to college, his father was a self-taught mechanical engineer with an entrepreneurial streak. When Noller was nine, the family moved a few miles east to Orinda, where they were the “least affluent family in that upscale community.” As a high school senior, he was delighted to discover the biochemistry department at UC Berkeley, “because I realized I wouldn’t have to give up either biology or chemistry if I wanted to be a scientist.”

Noller credits great mentors, hard work, and a fair smattering of good luck and serendipity with helping him along in life and work. When his adviser at UC Berkeley saw his senior-year grades, he said, “Well, I guess you won’t be going to graduate school!” But another professor mentioned a new molecular biology institute at the University of Oregon; Noller was surprised to be admitted (“I thought they’d made a mistake”). He went on to earn his doctorate in four years.

“It was more like an artist’s studio than a factory or a laboratory,” Noller says of Oregon’s Institute of Molecular Biology, where potlucks and jazz punctuated freewheeling scientific discussions. “My adviser, Sidney Bernhard, threw me in the deep end of the pool, figuring I was smart enough to ask questions. He wasn’t a micromanager. It was disastrous for a while, but I found my way.”

If science and jazz are the rhythm of Noller’s life, fast cars are the melody. He began hanging out with friends who were building and racing sports cars during high school; he links landmark moments in his life to the car he was driving. He has a deep and lingering appreciation for the “classic Bentley” owned by ribosome researcher Alfred Tissieres five decades ago, and he vividly recalls attending the Grand Prix of Monaco; the computer servers in his lab are named after legendary Italian race-car drivers. Today, he owns a silver-gray 1966 Ferrari, as well as a red 1966 Maserati, both of which he enjoys driving on the winding coastal highway north of Santa Cruz. “Totally different experiences!” he says when asked to compare the two, exhibiting the loyalty of a parent asked to pick a favorite child.

Noller’s encounters with the bohemian include an extraordinary visit to Ken Kesey’s home in La Honda on the day before he left for a postdoctoral fellowship at Cambridge University. Noller spent the afternoon and evening with Kesey and his associates, screening rough footage from their 1964 cross-country road trip and sleeping in the cabin where he believes Kesey wrote Sometimes a Great Notion—“one of the great American novels.” A complex diagram of the book’s plot tacked on the wall reminded Noller of a molecular structure. “It was a lot of fun,” Noller says with an enigmatic smile.

“My career has been marked by a series of accidents and luck. I've always had my eyes open to possibilities.”

Early on at Cambridge, a shudderingly uncomfortable brush with greatness changed the trajectory of Noller’s career. At a sherry party at King’s College, the legendary biologist Sydney Brenner approached Noller and asked what he planned to study. Upon hearing about Noller’s investigation of a metabolic enzyme, he bristled, “That’s stupid! Why don’t you study something interesting, like the ribosome?” Noller was shattered, but he couldn’t stop thinking about the ribosome. His fate was cast.

“My career has been marked by a series of accidents and luck, but you have to realize when that’s happening. It’s an opening,” he says. “I’ve always had my eyes open to possibilities.”

Looking back on his decision to join the faculty of UC Santa Cruz just three years after the university opened its doors, Noller is grateful for the freedom he experienced. “I can’t know for sure, but I have a feeling that our early ideas might not have gotten off the ground if I had been at a school like MIT or Harvard. Here, there was nobody to tell me, ‘That’s a bad idea.’ For a scientist, it’s very good to have a feeling that you’re not restricted in your thinking.”

Standing in the living room of his Bonny Doon home, where clerestory windows light up the redwood-paneled sitting area and expansive windows offer sweeping views over the forest, Noller says he has never been tempted by offers from other schools.

“My office and lab are on the most beautiful campus in the world, where walking to the library is practically a religious experience,” he says. “My commute is 10 minutes through the woods on a road that I sometimes drive dangerously fast. There’s one stop sign between my house and the campus. I couldn’t have scripted a better place to be an academic.”

“I look forward to coming to the lab every day. The fun never stops.”

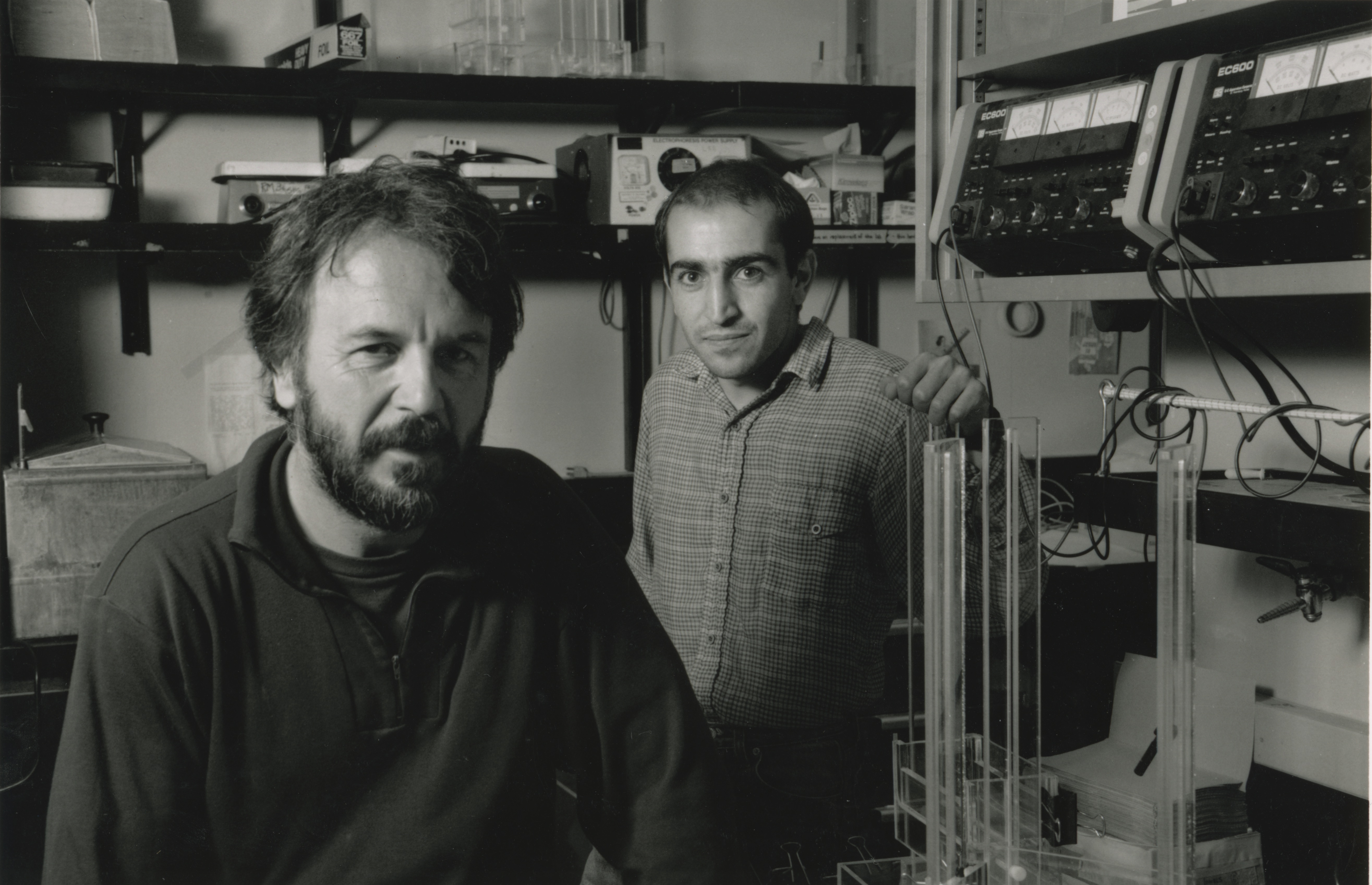

Today, Noller is at the center of an international constellation of superstar biochemists, many of whom express surprise about the contributions made by undergraduates in his lab. “In the beginning, it was mainly undergraduates,” he recalls. “The lab was tiny and cramped, and we worked in shifts.”

The Breakthrough Prize recognizes the totality of the effort, says Noller—not only his contributions, but those of more than 150 undergraduates, graduate students, postdocs, and visiting professors who have worked in his lab over the years.

Noller, who has held the Robert L. Sinsheimer Endowed Chair in Molecular Biology since 1987, is still in touch with most of those people. More than 100 showed up for a reunion three years ago. Many remain colleagues in molecular biology, while others have become major players in other fields. “I’m glad they’ve found something they love, that they’re good at, and that they’re having an impact on science,” he says.

“I’ve met a lot of towering figures in science, and I would not put myself in that category,” he says. “These people are gods. They will always be gods to me.” Then Noller recounts an exchange with his fellow ribosome researcher Peter Moore of Yale University. “We were at a conference about 10 years ago, and when the attendees got off the bus, I turned to Peter and asked, ‘Where are all the old guys?’ He turned to me, and said, ‘Harry, we are the old guys.’”

Today, retired from teaching, Noller shepherds his team—largely postdoctoral researchers—with the same hands-off management style that allowed his ideas to flourish. “I want to bring out the best in them, to optimize who they are as scientists,” he says.

“I look forward to coming to the lab every day. The fun never stops.”